Tara Snyder has been many things: a mom, a business owner, a soccer coach – and a prisoner.

In October 2018, Snyder was arrested for forgery and theft after it was discovered she had been using money from a school fundraiser to help a struggling friend. Her bond was initially set at $20,000, and she was held in Logan County Jail for three months.

While locked up, Snyder missed her 11-year-old daughter’s musical and her son’s football games. She slept next to women vomiting from drug withdrawal and was so ashamed she couldn’t bring herself to see her mother when she visited.

At this point, Snyder hadn’t been tried. She was still presumed innocent, but because she couldn’t pay her $20,000 bond, she couldn’t care for her children or run her advertising business. And Snyder’s case is only one of thousands like it in Ohio.

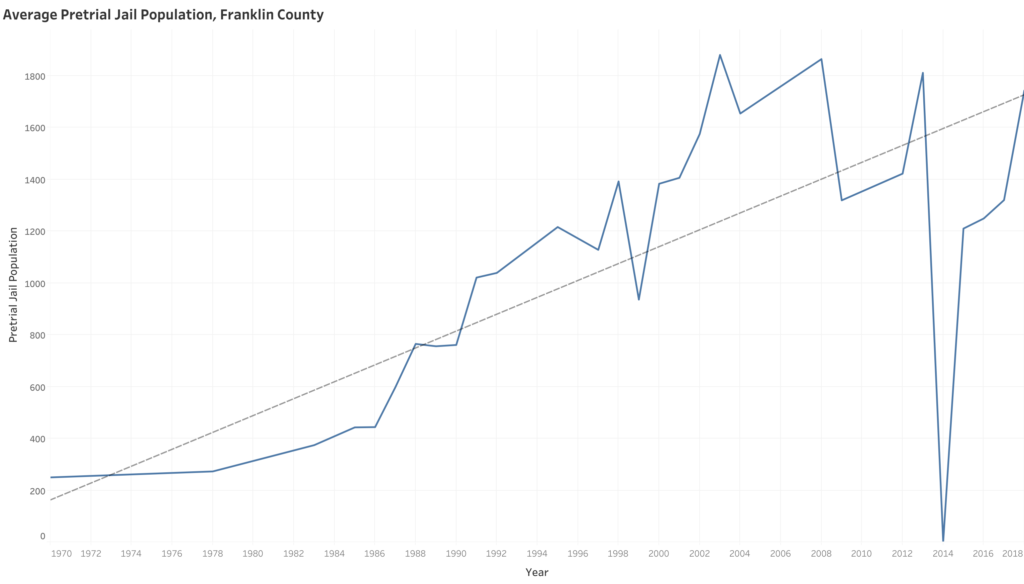

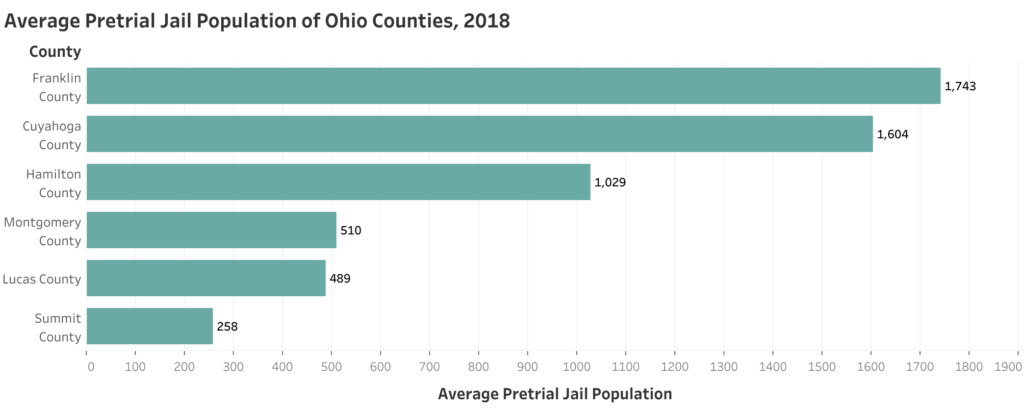

According to an analysis of incarceration data, the average number of people incarcerated before their trial in Franklin County was 1,743 in 2018. That’s an almost sevenfold increase in the number of people jailed since 1970. The data was collected by the Vera Institute of Justice, a national criminal justice reform research and advocacy organization.

Although they are legally innocent and have the right to a speedy trial, people jailed before their trials can remain locked up and cut off from their communities for indefinite amounts of time. The growth of pretrial detention in Franklin County has mirrored increases seen across the US, with rates of pretrial detention in the country roughly quadrupling since 1970, bringing the total number of people locked up before their trials in the US to over 440,000.

Crime rates of all types have gone down steadily in Columbus and throughout the US for several decades, but more people are locked up now than were 20 or 30 years ago. Experts attribute this increase to tough-on-crime politicians and policies, expanded jail budgets and infrastructure, and a greater desire among the public to “keep criminals off the streets.”

Pretrial detention results in lost jobs and wealth extraction from the poorest and most vulnerable citizens, and evidence suggests these downsides actually increase crime. While advocacy groups fight to reform the bail system, some argue pretrial detention helps maintain public safety by potentially keeping criminals in jail despite the lack of evidence supporting this claim.

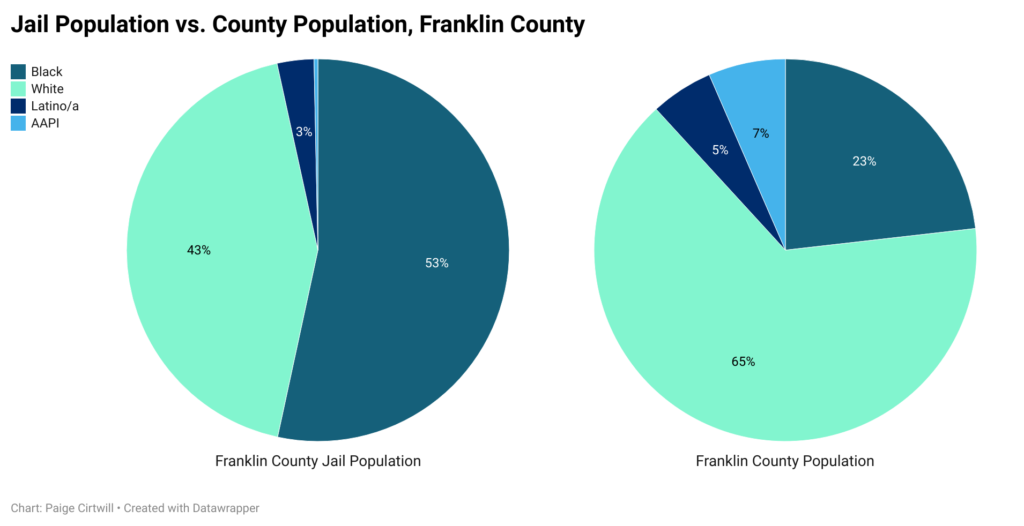

Jailing in Franklin County also varies significantly by race. The analysis found that in 2018, Black inmates accounted for just over half of all people jailed in Franklin County despite making up under a quarter – 23 percent – of the county’s population.

“Every single day in Ohio, there are hundreds, thousands of people appearing in misdemeanor courts on those low-level charges, all the way from speeding tickets to shoplifting to simple assault to disorderly,” Tim Young, director of the Office of the Ohio Public Defender, said. “Against the law? Yes. Huge safety violations? No. Is the public at some main risk? No, not really.”

How Bail Works

Before the cash bail system took hold in the U.S, people charged with a crime were usually released on their own recognizance or were required to have a friend or family member promise they would pay the court if the accused failed to appear.

These types of bonds are still around, at least in spirit. Today, the accused might be released on recognizance bond, which is just a promise he will appear for his court dates. Recognizance bond is typically granted to defendants with minor misdemeanor charges such as traffic violations.

Because many defendants were unable to pay their full bail amounts up front, bail bonds became a lucrative industry in the 1900s. If defendants couldn’t afford their own bail, they could pay a bondsman a fraction – usually around 10 percent – of the total bail amount and the bondsman will loan out the full amount to the court. After the trial, the court returns the bondsman’s money, but the bondsman keeps the payment from the defendant.

Depending on the severity of the crime, the accused might instead be detained without the option of paying bail. Ohio law states that those accused of a crime can’t be denied bail entirely unless the judge believes there is “clear and convincing evidence” that the defendant is guilty, is a danger to an individual or the community, or is a flight risk.

The bail amount is set during the defendant’s first appearance in court. There are some guidelines governing how bail is set – judges are supposed to look at the defendant’s legal history and whether they will flee or endanger someone – but bail amounts can vary wildly depending on the judge, Mark Collins, a criminal defense attorney in Franklin County, said.

“The issue is, there’s 15 different municipal judges who do arraignments and initial appearances and they all set different types of bonds,” Collins said. “You may have a person get arrested today and have a court hearing tomorrow at a municipal court, that person might get a $1,000 bond. If it happens a week from now and there’s a different judge, it could be $50,000.”

Collins said bail might be higher depending on the type of crime. If it’s a low felony but involves a more controversial aspect, like guns or drugs, bond might be higher.

Bail amounts can even differ based on where the accused is from. People in urban areas might get a lower bond because the crimes they’re suspected of committing are more routine, Collins said, but in rural areas, the price might be much higher.

According to a recent Ohio Supreme Court ruling, “the sole purpose of bail is to ensure a person’s appearance in court,” and Ohio law requires that if the judge isn’t choosing to detain the defendant, he should be released under the “least restrictive conditions” that still ensures his appearance in court and protects public safety.

Of course, all of this assumes the defendant has his first hearing quickly after being arrested. If he gets arrested on the weekend – on a Friday afternoon the week before there’s a Monday holiday, for example – he’ll be held all weekend, Collins said.

For people who are released on recognizance or are able to pay their bail, Franklin County has recently started following the federal court system in following up with defendants and trying to connect them to counseling, drug addiction services, and legal services.

If the defendant isn’t released on recognizance or if he doesn’t have the money, he goes to jail.

Tough on Crime

The increase in pretrial detention rates in Columbus is significant, but it’s more or less in line with similarly-sized cities. The US as a whole experienced a fivefold increase in pretrial jail populations between 1970 and 2015.

Interestingly, jail populations in the biggest cities leveled off and even started declining in some places in the early 2000s, but jail populations in smaller cities like Columbus and others throughout the Midwest continued to stay high. The jail population per 100,000 residents for rural counties and small cities has been higher than that of big cities since 2001.

“The Midwest used to have much lower incarceration rates, and now it’s looking more and more like the incarceration rates you see in the South,” which are notoriously high, Jacob Kang-Brown, senior research associate at the Vera Institute of Justice, said.

Judge Mark Hummer, administrative and presiding judge of the Franklin County Municipal Court system, partially attributed the massive increase in pretrial jail populations in Columbus to the fact that the population of Franklin County is larger now than it was then.

He’s right that Franklin County has a large population – larger than Cuyahoga and Hamilton County, the county seats of Cleveland and Cincinnati, respectively – but this only explains a small part of the increase. Franklin County’s population increased by roughly 57 percent since 1970 – a far cry from the sevenfold rise in pretrial detention rates.

Also important to note is that the pretrial detention rate grew so significantly during a time when the growth of racial minorities was responsible for almost all of the county’s population increase, while the white population remained virtually unchanged.

The nationwide spike in pretrial detention and incarceration more generally, which came to be known as “mass incarceration,” coincided with disinvestment in public education and health care and a decline in the number of good-paying, low-level jobs that historically supported people with little to no education, Kang-Brown said.

As crime rates shot up throughout the 1970s and ‘80s, there was also a cultural and political turn toward harsher, more punitive solutions. Politicians angling to appear “tough on crime” began advocating for harsher detention and sentencing policies most clearly depicted in the War on Drugs during the late 1900s and the 1994 Crime Bill.

“I think that there was a conscious move beginning in the ‘70s and ‘80s to lock more people up, and that included pretrial detention,” said Wanda Bertram, communications strategist for the Prison Policy Initiative, a nonprofit research and advocacy organization.

“I think it was a mounting campaign by prosecutors, law enforcement, and certain elected local officials … where they said, ‘For the sake of public safety, certain people who are simply career, habitual criminals cannot be allowed to go free before their trial.”

The crime bill included an increase in federal funding for law enforcement agencies and, importantly, a program through which states could receive funding for expanding their prison and jail infrastructure and incarcerating more people. This incentive was so strong that for a period of time after the bill’s passage in the mid-1990s, a new prison opened every 15 days on average.

Class and Race

Snyder says she got lucky, relatively speaking – she came from a well-off family, owned a business, and had some family members who were willing and able to care for her kids – but most of her fellow inmates didn’t share those advantages. The way the legal system currently works, a well-off person charged with a crime may leave jail the same day but another person charged with the same crime could be locked up for weeks.

“We conflate money with safety. And that’s just the most false assumption ever.” Young said. “If we release some sociopath back into society because he has access to a trust fund, how have we accomplished anything?”

Most people in jail pretrial are there solely because they’re poor. A national study found roughly 90 percent of people jailed pretrial can’t afford their bail. One report from New York found that even when their bail was $500 or less, 40 percent of detainees couldn’t pay and remained locked up until their trial ended.

“You have these cases where bond has been set at $1,000 or $2,000 or $5,000 everyday, and people are like, ‘Oh, well that’s not a very big number,’” Young said. “That’s an impossible number! 70 percent of the people who go through criminal courts need a lawyer appointed for them. That means they make very close to or below poverty.”

It’s well-known that cash bail creates racial disparities in incarceration that intersect with class ones. Black people constitute just over half of Columbus’ jail population despite making up under a quarter of the city’s population. This is roughly in line with the US overall, where Black people make up around 35 percent of the total jail population but constitute only 12 percent of the population.

On the other hand, Latino and Asian American people are underrepresented in Columbus jails. Latino people and Asian Americans each make up around five percent of Franklin County’s population but constitute less than three percent of the jail population.

Racial disparities in incarceration go back centuries. After the Civil War, Black codes – laws that governed Black people in the South – were enacted, criminalizing Black people for offenses such as being unemployed or attending gatherings with white people, largely for the purpose of leasing them to plantation owners, essentially enslaving them once more.

While Black codes are no longer on the books, their legacy remains in the legal system. That legacy is expressed through overpolicing of communities of color and the fact that white and Black people use drugs at roughly the same rates but Black people are incarcerated for drug offenses much more frequently, said Meghan Guevara, executive partner at the Pretrial Justice Institute, a research and advocacy non-profit.

“We know that people of color, particularly men of color, are more likely to be arrested if they come in contact with the police,” Guevara said. “Once they are arrested, they’re more likely to get higher bond amounts and more likely to be convicted. So at every opportunity to make a decision, there are additional disparities introduced into the system that result in those higher incarceration rates.”

When the pandemic began in March 2020, the Franklin County court system shut down and people in jail awaiting their trials had court appearances postponed. The Court of Common Pleas started hearing a limited number of cases again June 1, 2020 – almost three months after cases were postponed.

Jury trials were unilaterally postponed again beginning Nov. 23, 2020 and didn’t resume again until Jan. 29, 2021. Even when they resumed, however, only a handful of select cases were tried until April 5 of that year when the courts began hearing all jury trials once again.

This created a significant backlog of cases in Franklin County and across the country. In one instance, Jermaine G. Johnson, who was charged with murder but eventually acquitted, spent over three years in Franklin County jail before his trial – a wait largely caused by the pandemic.

Even before the pandemic, people in jails could be forced to stay for weeks or months. The ACLU of Ohio found that the higher a defendant’s bail, the longer they stay in jail. In Franklin County, people charged with felonies who are able to post bond stay in jail for nine days on average, while people who can’t pay stay for over a month.

“One of the effects is people are separated from their families, they’re disconnected from their jobs and their livelihoods and they may lose apartments or cars or something like that,” Kang-Brown said. “That can have a huge impact on someone’s life.”

This issue is compounded by the higher toll bond payments take on poor people. The wealthy can post bond and leave jail quickly after being arrested with relatively little disruption to their lives, but poorer people often can’t afford it and may be unable to communicate with employers or family members.

When defendants are jailed before their trials, it also makes it much harder for them to help put together a legal defense which would help them prove their innocence, Collins said.

“Basically, if you’re rich, I’m going to get you out of jail, I’m going to do everything proactive, and you’re going to be in a much better situation to resolve your case,” Collins said. “If you’re poor and you can’t get a reasonable bond, then every day you’re in there, you’re like, ‘How do I get out?’”

People who can’t get out on bond will be much more incentivized to accept a plea deal. Collins said this can mean more people in prison or with charges on their records even if they’re innocent.

However, taking every case to trial has its problems, too. Hummer said “you couldn’t possibly have every case be at trial in our county” because there simply aren’t enough judges, prosecutors and attorneys to take them on. For some people, Hummer said pleading down to get out of jail can be beneficial because it resolves the case.

Still, leaving work with no notice, being unable to care for children, or missing rent or car payments are all common outcomes of pretrial detention that most people simply can’t afford – and the problems don’t end when they leave jail.

“Then you come out and you try to find a job and you have this on your record while you’re looking for a job,” Collins said. “Even if you win the case and it’s dismissed, and you’re not guilty, then they do a record search or someone Googles you and says, ‘Oh, [you were] charged with this back in 2022, even though they’re not guilty.’ So that cycle is very vicious.”

Does it Work?

Based on research from cities that have changed their bail policies, locking up more people before their trials is unlikely to make communities safer. After reforming bail policy in 2019 to release more people, a report from the New York City comptroller found that rearrest rates for New Yorkers awaiting their trials remained virtually unchanged before and after the reforms were implemented, indicating that the new bail policies did not lead to an increase in crime or harm public safety.

“The number of people who are released pretrial who go on to get rearrested before they come back to court for their original hearing, it’s in the range of one to two percent,” Bertram said.

Analyzing pretrial data from four Ohio counties, the ACLU of Ohio found only around 40 percent of people in jails were there on felony charges, and even then, the most common felony charge was drug possession.

Jailing people before their trials is also expensive, costing Ohio taxpayers hundreds of millions of dollars a year. A report from the ACLU of Ohio found that the daily cost of keeping a single person in an Ohio jail could be as much as $87.

Ostensibly, the sole purpose of cash bail is to ensure the defendant shows up for their court dates, not to keep them in jail, Young said. Maintaining public safety is better accomplished when judges use conditions of release like ankle bracelets, curfews, and travel restrictions.

“Those are the kinds of safety conditions they directly relate to, ‘Will you be able to go out and hurt somebody again?’” Young said. “Paying me a million dollars to get out of jail does nothing to stop you from hurting somebody again.”

Living conditions in jails are often worse than in prisons, and inmates say they prefer it there. Snyder said in jail, the inmates weren’t offered underwear to wear, and she slept and spent her days in a large, open room full of bunk beds.

“Being stuck in that little tiny cell block with the same women, day after day after day – it’s rough,” Snyder said.

Despite the high price tag associated with pretrial detention and the lack of evidence that jailing people makes communities safer, Franklin County recently built a new jail, called the James A. Karnes Corrections Center, which is slated to begin housing inmates later this year.

The new jail cost around $360 million and was funded by sales tax and bonds, Tyler Lowry, director of public affairs with the Franklin County Board of Commissioners, said in an email. It will eventually be able to hold over 1,200 people.

The new facility is a major upgrade compared to the two old Franklin County jails, Major Chad Thompson, an officer with the Franklin County Sheriff’s office, said. It includes 16 units with different security levels and purposes as part of the jail’s “strategic inmate management” policy.

In the minimum security units, there are no cells, so inmates and officers can interact with each other freely. The unit also has a dedicated classroom, recreation space, and plenty of windows to let in natural light, Thompson said.

“The piece of the population that comes in, generally speaking, goes back into the community,” Thompson said. “Such a small percentage that come to jail are actually the Hannibal Lecter’s of the world. Generally speaking, they’re not, and so we shouldn’t treat them like it.”

Other features of the new jail include upgraded technology to facilitate online classes and video calls, as well as a Take 10 room – a private room where inmates can go to be alone, for example, if they received upsetting news. The technology upgrades should also help defendants, lawyers, and judges alike by making it easier to connect outside of the courtroom, Collins said.

“If you get arrested on a Friday … at 2:00 in the afternoon, why can’t we do a hearing Friday at 4:00 if there’s a video system?” Collins said.

While the new jail features a number of necessary improvements, some advocates are skeptical about building new jails and prisons. Kang-Brown said when new jails and prisons are built, they tend to fill up.

“There’s a lot of standard thinking that’s like, ‘Oh, it’s prudent to plan for the future, we’re going to have a population increase, we should build a larger jail,” Kang-Brown said. “But in doing so, you’re planning for a future with more people in jail, and you aren’t planning for a future with better schools, better libraries, more funds for health and social services, the things that people really want as local policy priorities.”

The old jail in downtown Columbus will close and be demolished, with plans to build in its place a child care facility for county employees and families visiting the courthouse, Lowry said in an email. The Jackson Pike jail will remain in use.

Reform

Efforts to reform bail policy in Ohio have been gaining more traction in recent years. Two proposed bills, House Bill 315 and Senate Bill 182, would require Ohio courts to decide whether someone charged with a crime will be released within 24 hours of their arrest.

If the court decides the accused shouldn’t be released, the court must hold another hearing soon after the first to determine either what conditions the accused can be released under or if they will be detained until their trial.

“[The legislation] would create a lot of opportunities for people to not be detained pretrial simply because of wealth, and also would eliminate the opportunity for people to be released simply because they can afford to pay a high monetary bond,” Guevara said.

Guevara also points out that the bills were written with input from advocacy organizations and community groups, including the Ohio ACLU.

Even if cities wanted to reform or eliminate cash bail (which most have not attempted), there’s still the matter of public safety. While the vast majority of people released pretrial aren’t charged with another crime before their trial, many people fear an increase in crime they anticipate will occur if it’s easier to leave jail after arrest.

Crime rates in areas that have reformed bail policy stayed relatively stable before and after the reform, with the exception of New York state, which saw an increase in crime, followed by the reversal of the reforms a few months later. Still, there has been pushback to criminal justice reform efforts across the country, and in Ohio.

When the Ohio Supreme Court ruled in January that a judge’s decision to set defendant Justin DuBose’s bail at $1.5 million was excessive and unconstitutional, it prompted Ohio Attorney General Dave Yost and other Republican politicians to propose amending Ohio’s constitution to make it easier to jail people pretrial, citing public safety concerns.

Young and Collins say there are better ways of keeping people safe while protecting the rights of the accused. For instance, a judge can require that certain “conditions of release” be met for the accused to go free, which include ankle monitors, required daily check-ins with pretrial services or law enforcement, or house arrest. Judges can also hold preventative detention hearings if they feel the defendant is too dangerous to be released.

Doing the Work

While incarcerated, Snyder began blogging about her experiences in jail, writing about the women she met and how she stayed connected to her family. Her work was eventually discovered by the ACLU of Ohio, and she is now collaborating with them to start an online magazine to tell the stories of people impacted by the criminal justice system.

Snyder said they’re thinking of calling it the Cardinal Project, a reference to both the Ohio state bird and Maya Angelou’s autobiography, “I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings,” implying people in jail are like caged birds.

She said it’s important for people to write about their experiences with the criminal justice system to raise awareness and help reduce stigma.

“You’re so terrified and ashamed, when the thing goes down, but when you actually own it and you can actually talk about it openly, nobody can hold that power over you anymore,” Snyder said. “The system is built to keep you down and make you feel that shame all the time. But when you take it back, you’re like, ‘Okay, I did it, but you know what? It’s in the past, I’ve moved on, you can’t hold that over me anymore.’”